Is the text on your website ADA-accessible?

Marc Rust,

Senior Creative Director at Boston Interactive

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) has changed the lives of countless Americans by prohibiting discrimination against individuals with disabilities. But while the more prominent protections focus on employment nondiscrimination and building access, the ADA also has major implications for websites and other digital design.

It’s important for businesses and organizations of all kinds to understand and meet these standards. But it’s especially crucial for the fields of finance, healthcare, education, and certainly government. And while the ADA guidelines can seem overwhelming at first, in reality they simply prescribe, in specific ways, a thoughtful, clean design that prioritizes all users’ experiences.

The standards.

The ADA focuses on four general principles that provide a road map for designers and developers working toward ADA accessibility: Websites must be perceivable, operable, understandable, and robust. These may seem like simplistic goals, but for people with visual, hearing, or physical challenges, these essential elements are often unintentionally compromised by everyday design choices.

Color alone should not be used to indicate important phrases within text, to distinguish instructions or calls to action, or to indicate when an action has been completed (clicking a button, for example).”

Each of those principles is supported by 12 specific, actionable design and usability recommendations. Conformance to these recommendations is rated on a scale from Level A to AA and finally, AAA. Level A recognizes that the design meets a basic minimum standard for the given guideline, and level AAA indicates an ideal solution for the given guideline. (Level AA is, obviously, a midpoint between the two.)

ADA accessibility isn’t enforced by the government, per se. Unlike the case of GDPR in Europe, the government doesn’t mandate that companies and organizations update their designs to follow the standards. Instead, compliance is often enforced through lawsuits brought by private parties on the grounds that a company’s web experience is not ADA-accessible.

This is all quite a bit to digest, and there are numerous resources offering detailed explanations of the guidelines and their respective criteria for conformance levels. But for the purposes of this article, let’s focus on three general guidelines related to text.

How to use color to make your website ADA accessible.

Designers have long used color to establish hierarchy and differentiation on a page, but doing so can impact readability for people with visual challenges, namely color blindness. The ADA stipulates that color should “not be used as the only visual means of conveying information, indicating an action, prompting a response, or distinguishing a visual element.”

In other words, color alone should not be used to indicate important phrases within text, to distinguish instructions or calls to action, or to indicate when an action has been completed (clicking a button, for example).

Instead, designers should solve these issues by tactfully using a range of weights, sizes, and styles to indicate headings, instructions, and calls to action. The Harvard Medical School website is a good example of this principle in practice. A single, versatile font family can provide all the variety you need, but designers can approach these use cases by using different fonts for different purposes.

And to be clear, this can all be done in addition to using color. The ADA guideline simply says color can’t be the only distinguishing characteristic of a piece of text.

“Back in the day, we used color to show hierarchy,” says Marc Rust, Senior Creative Director at Boston Interactive. “Now we use font size, rather than color, to maintain readability and ensure ADA accessibility. Font choice matters more than ever to make the design work.”

How text contrast makes your website ADA accessible.

Contrast is another important element of the ADA, and it goes hand-in-hand with color. The ADA has specific recommendations for contrast ratio, with the goal of creating enough contrast between text and its background so that it can be read by people with moderately low vision.

The prescribed ratios vary based on the size of the text, and higher conformance ratings require larger ratios. There are also numerous online testers that let you experiment with text and background colors to see the ratio and the rating a particular combination would earn.

It’s also important to avoid all-caps treatments, especially in smaller text sizes. The consistent letter height of all-caps text makes it difficult for people with vision impairments to discern individual letterforms, or even recognize the blur of color as a word. All-caps text should only be used at large sizes, if at all, but even headlines are better off written in sentence-case.

“Especially in smaller text, all-caps text isn’t readable to people who are visually impaired,” says Marc Rust, Senior Creative Director at Boston Interactive. “They just see it as one block. You shouldn’t use all-caps at all under 12pt.”

This guideline means it’s essential to choose fonts that bolster the contrast on your site. Ultra-thin weights, for example, diminish the effectiveness of your contrast ratio because of their design, even if the ratio is technically within the ADA’s parameters.

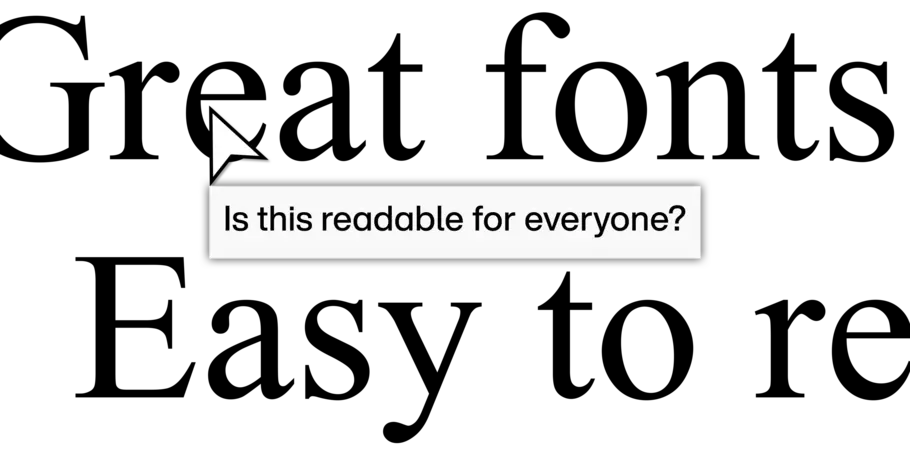

Similarly, a slab serif may not be the solution either if its design is too heavy for visually impaired people to read. Instead, look for highly legible fonts with large, open counters, ample lowercase x-heights, and character shapes that are obvious and easy to recognize.

Font choice is crucial, and while the ADA does outline specific, measurable guidelines for contrast, there’s a fair amount of subjectivity involved as well. “Choosing the right font isn’t entirely scientific,” says Rust. “In fact, it’s largely artistic.”

How live text makes your website ADA accessible.

The ADA places importance on enabling people to use screen readers and other tools when they visit a website. The key to making this work is simple: Use live text.

For the uninitiated, live text means the text has been coded into the site. From the user’s perspective, live text can be highlighted, copied, and pasted just like text from a Word document. Most text on modern websites, particularly body copy (such as this article), is live text.

Text can also be embedded into images. This is less common today and is typically used in headings and other “decorative” applications. The problem is that screen readers, and other auditory devices can’t “read” text on an image. So the ADA stipulates that actual live text should always be used to convey information. Images of text are allowed as “pure decoration” or “where a particular presentation of text is essential to the information being conveyed.”

Using live text also enables that text to be resized easily. Per the ADA’s guidelines, text should be resizable “without assistive technology up to 200 percent without loss of content or functionality.” This type of usability is common with mobile-first design, but the ADA guidelines put a firm stake in the ground.

“A mobile-first approach is a good way to look at text,” says Marc Rust, Senior Creative Director at Boston Interactive. “Think of how the text will be used, not about the document size and whether it’s on mobile, desktop, or some other format. Text should be thought of as a responsive component that adapts to the user’s need.”

Balancing form and function.

While the guidelines may seem granular, in reality, much of this is simply solid, user-friendly design in practice. Many of the standards outlined by the ADA—contrast comes to mind—are things designers should be doing anyway, and likely are, albeit perhaps not to the precise levels required here.

That said, it’s essential to have the right tools if you want to balance ADA accessibility with on-brand design. One of those tools should be a robust font library that offers a range of highly legible fonts in a range of styles. While no font is ADA-approved in any official capacity–there’s no certification program or anything like that–these guidelines can help you identify fonts that fit the description. A well-rounded library with robust options for web fonts will get you well on your way to developing accessible web designs your customers will appreciate.